Defining a Category: Using Behavioral Science to Further Product Naming Conventions

Occasionally new subcategories will emerge driven by technological innovation that are similar to a previous category but also different in critical ways. The challenge then for product managers and marketers becomes what to call these new products. Consider, for example, how elements of the traditional laptop and tablet have converged to form a new 2-in-1 category of hybrid computers. Microsoft launched the Surface Pro Series in 2013, bringing awareness to this category, and by 2015, hybrids had become the fastest growing segment of the mobile PC market. However, challenges in communicating these forms still existed. Do you associate them with tablets, which are more popular for leisure devices, or laptop computers, which have stronger associations with work occasions? The reference frame that the product or marketing manager chooses will have important implications for how the consumer views the product.

So when the technology in a category advances rapidly, how should managers consider whether to associate or disassociate with previous similar categories?

The Yale Center for Customer Insights (YCCI) recently tackled this question through research conducted with Wildtype, a San Francisco startup that is developing a new line of seafood grown from cells in bioreactors. On the one hand, Wildype’s products look and taste like a fish that was caught or farm-raised, with similar nutritional and textural properties. On the other hand, they are distinct. Wildtype seafood is more sustainable and the fillets don’t come from a whole fish; instead, they are grown from fish cells in a system that looks a bit like a beer brewery.

A Behavioral Perspective

While the perfect category name is a subjective assessment, Behavioral Science helps us better understand how consumers might assess a name in the marketplace. Behavioral Science suggests that people process information in two ways. The first, “System 1,” is rapid, intuitive, and automatically drives many of our everyday thoughts. The second, “System 2,” is slow, deliberate and requires more mental resources. Most consumer decisions are processed using System 1 processing. When a consumer encounters a product in the marketplace, they need to be able to very quickly and intuitively determine some basic characteristics of the product and how it might be used. They also need to determine what it is not.

Consider, for example, the newly launched Veggie Dog from IKEA, a product made with vegan ingredients such as kale and red lentils. While the name immediately brings traditional hot dogs to mind, it’s also immediately clear from the use of the word “veggie” that this is a plant-based alternative. Similarly, McDonald’s recently tested a plant-based burger featuring Beyond Meat which they called the PLT. While the name brought to mind associations with the classic BLT (bacon, lettuce and tomato) sandwich, the “P” clearly indicated to consumers that the bacon has been swapped for another ingredient.

However, it’s not enough to merely associate with a category but also be distinct from it; the new subcategory name must also strive to create positive new associations. Synthetic diamonds may bring to mind an association with the word “diamond” while maintaining a distinction, but the word “synthetic” may have some negative attribution.

Creating positive associations while maintaining distinction can be tricky, but when marketers walk this line successfully, it can be very impactful. In the late 1960s, 7Up repositioned their brand from a tonic that was often associated with upset stomachs to the “Uncola.” By anchoring the brand to the cola category, but at the same time differentiating it from the dominant players, 7Up was able to catapult sales and become one of the top soft drinks on the market.

How Brands Should Think About Category Labels

For brands entering a new category, drawing clear distinctions from existing categories while generating positive associations – and avoiding negative associations – can be especially challenging.

This is the core challenge for Wildtype, whose products are not yet associated with a common category (for example, as Cheerios are to cereal). Currently there are no seafood products on the market in the U.S. that are produced by cultivating cells, and no conventional nomenclature exists for a product of this type. Wildtype must then work to develop a category name that helps consumers to identify their products while meeting strict regulatory guidelines. In order to drive commercial success, Wildtype also needs to identify which potential names appeal to consumers and drive purchase intent.

But how do you begin to identify a name with appeal when consumers lack general category awareness? To help address this question, we have identified robust methods that brands can use to inform category labeling:

First, explore how consumers and the industry are currently talking about the nascent product category. Look at how they are using natural language in social media and search to describe both their goals and the solutions currently in the marketplace.

To understand why listening to the consumer is so important, take the example of Poppi, a new “better for you” soda that has gained popularity. What makes Poppi different from other sodas is that it features apple cider vinegar, a key driver of gut health. When Poppi began, they prominently featured “Apple Cider Vinegar Beverage” on their packaging. Demand was modest. During a brand refresh, the team at Poppi dropped the “Apple Cider Vinegar Beverage” tagline and began referring to the product as a “Functional Soda” or “Prebiotic Soda.” Early signs suggest that the shift toward labels such as “Functional” and “Prebiotic” has paid off for Poppi. Increasing consumer demand has brought competitors such as Olipop to the space and, today, the functional soda category is a fast-growing beverage segment.

To understand how people might be talking about Wildtype’s products, the YCCI team first searched a broad list of terms using Brandwatch, a social listening platform, to understand how often certain terms were used online, as well as measure positive and negative sentiment based on the language and context used in social media posts. Our search suggested that while no one name was widely used to describe this category, certain terms evoked strong reactions. For example, “lab-grown seafood” carried significant negative sentiment: 39% vs. an average of 5% negative sentiment among the other terms. It’s important also to consider how consumer usage of various terms is evolving. While this search was done looking at a historic period, brands should continue to track changes in consumer perceptions in real time as preferences can quickly shift.

Test different names to assess consumer response, measuring for both understanding and appeal. It is critical at this stage to select the right benchmark.

Consumer testing provides a unique opportunity to learn about your consumer without the risk of a full-scale launch. Once a short list of names is developed, brands can quickly gather feedback from consumers to measure both understanding and appeal. But while online tools make testing easy and cost-efficient, the testing design is critical to gathering usable results.

Our design included 2 nationwide surveys in early 2021 with over 4,300 respondents. We designed mock product packaging and used a monadic design, and only showed respondents one package, so they were not comparing names against each other.

We also were careful to make sure we used a proper “control” condition so we could establish a baseline for understanding and appeal. The right control should capture, in a few words, the product category that you want to test. That then becomes the gold standard that you measure all potential names against, with the aim of getting an understanding as close as possible while maximizing appeal.

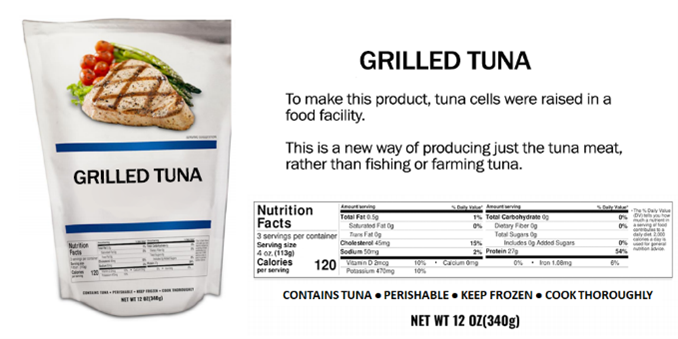

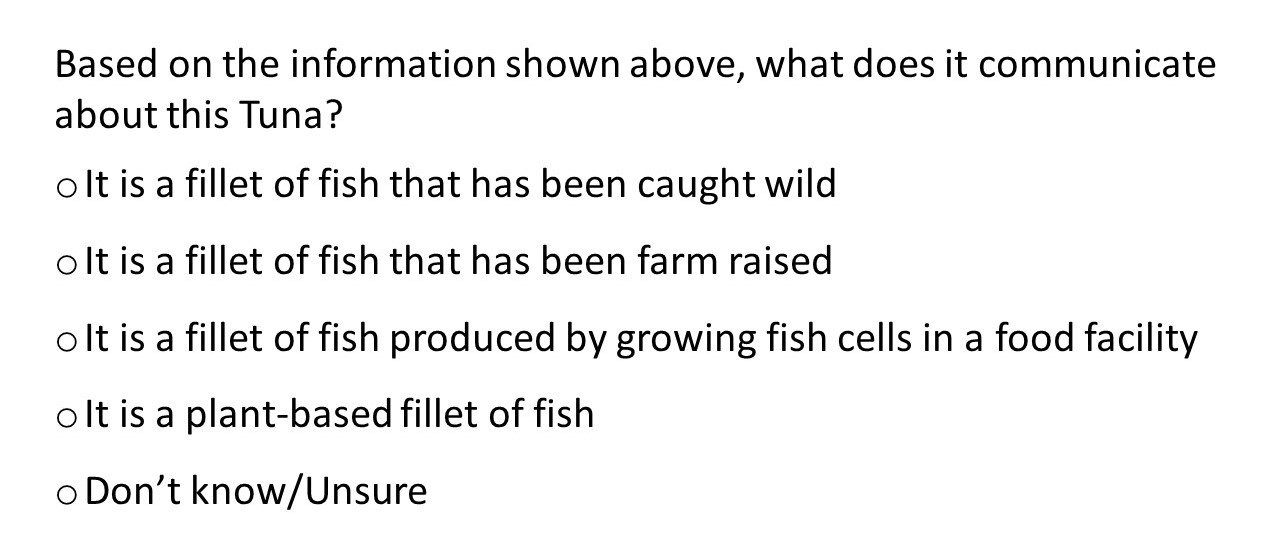

For Wildtype, in designing the control condition (Exhibit A), instead of using a name we described how the fish was made using a few lines of text, then asked them to identify the correct method from a short list of options, using the dependent variable in Exhibit A. As expected, almost all respondents in the control group were able to identify the correct method, giving us a benchmark to measure potential names against. 93% of tuna consumers and 97% of salmon consumers correctly distinguished the control from conventional seafood.

Exhibit A

In addition to ensuring that consumers could correctly identify the control, the team provided a “don’t know/unsure” option in all tests, which would allow us to better distinguish guessing or uncertainty from misunderstanding, a critical component to determining if a name might be misleading. We then tested a series of names that replaced the short description on how the product was made to measure how well these names communicated the distinctive properties of this new category.

Identify terms that may carry negative attribution, and use qualitative research to understand these negative beliefs.

During our testing for Wildtype, we found that some terms had cross-category ties to existing negative beliefs, as was the case with the term “bio-crafted.” While 68% of consumers correctly identified how “bio-crafted” seafood was made, only 23% were likely to purchase it, indicating that product understanding may in fact be detrimental to purchase intent if consumers link the product to existing negative beliefs. “Bio-crafted” seafood may have some sort of negative attribution which could be explored further in social media analytics or qualitative research with consumers.

Pay close attention to names that combine the familiar with the original. Research shows that these words tend to stick. Conduct further testing to explore associations and anticipate where potential misperceptions may arise.

While existing beliefs surrounding certain categories can prove useful for brands like 7Up, companies must be cognizant of how choosing a label adjacent to an existing category might be associated and how that might impact usage occasions. Consider, for example, the emerging category of “oatmilk,” a product that did not exist until 1990 but brought in sales of close to $215 million in 2020. Consumers often find the product next to the cow’s milk in the supermarket, but brands must ensure that consumers are aware that the nutritional profile differs from traditional dairy milk.

For Wildtype, this means ensuring that consumers with fish allergies don’t associate their products with plant-based fish alternatives. When we created a new term, Novari, to assess how a name with no established meaning would fare, we saw that while 45% of consumers found it somewhat or very appealing, only 3% displayed correct understanding of how it was made. Given that the term does not mean anything in the English language, it is interesting to find such a high level of appeal. If this were to be pursued as a product line name, it could be useful to identify the source of potential positive attribution, such as having a similar ending sound to the word “sushi” and what risks, if any, might be involved. However, given the low level of understanding, the term would not serve as a sufficient category label without critical investments and alignment from the industry to educate consumers.

Conversely, a compound descriptor, “cell-cultivated,” saw 32% of consumers found it somewhat or very appealing, while 79% correctly identified the product origin. The familiarity of the two words seems to adequately convey that cells are cultivated to produce the product, but more research would be needed to determine the source of any possible negative attribution.

Conclusion

We know from Behavioral Science that consumers do not always behave rationally and that many will make quick decisions based on their existing beliefs. Given this understanding, we designed our research not to identify one single name that would win all consumer hearts and wallets, but instead to understand how names impact product understanding and appeal, and what research methods were best positioned to address these questions.

For more details on our research design, methods, and results, please visit here.

To connect with someone at YCCI to discuss helping your company with designing and implementing research informed by Behavioral Science, please visit here.