Prof. Goetzmann Discusses Finance Practices in Mesopotamia

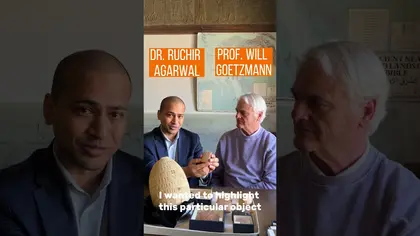

The Yale Babylonian Collection featured a series of videos of Prof. Will Goetzman discussing finance practices in Mesopotamia via their Instagram account

The Yale Babylonian Collection Instagram account recently featured Prof. Will Goetzmann, see below the series of video posts.

Over the next few posts, we’ll be looking at finance practices in Mesopotamia with the help of Prof. Will Goetzmann, Edwin J. Beinecke Professor of Finance and Management Studies at the Yale School of Management and author of Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible (2016).

Although concepts like compound interest, joint ventures, commercial law and international trade are familiar to us today, such practices have deep histories.

Prof. Goetzmann will discuss how ancient financial records are available to us from cuneiform texts starting in the 3rd millennium BCE and covering war treaties, trade between Mesopotamian entities and Dilmun, land transactions conducted by women, and business partnerships in the textile trade.

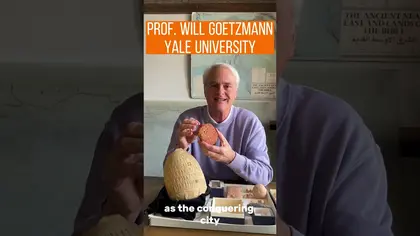

The earliest transaction records pre-date writing systems and go as far back as an estimated 8000 BCE. The system involved the use of clay tokens and envelopes called bullae, which were used to keep track of quantities of goods transacted and was widely used across ancient Western Asia for millennia.

more

The above image shows a modern reconstruction of how the system worked using an ancient cylinder seal and tokens and a bulla made from modern modelling clay. A number of tokens (representing, for example, quantities of livestock, grain or beer) were inserted into a clay envelope, which was then sealed with a cylinder or stamp seal to identify the sender. Sometimes the tokens were impressed on the outside of the envelope to indicate what was inside. The clay envelope could then be broken to ensure that the quantity indicated on the outside matched that on the inside.

Bullae continued to be used during the third and second millennia and were also later adapted to carry cuneiform tablets inscribed with letters, contracts or administrative documents. While the shape of these later envelopes was square or rectangular rather than spherical, the principle remained the same: to protect the authenticity of the envelope’s contents.

Archeologist and historian Denise Schmandt-Besserat theorized that the shape and design of these prehistoric tokens influenced proto-cuneiform signs.

Watch out for a reel with Prof. Will Goetzmann, where he explains how this system helps us understand the beginnings of the history of finance.

Cylinder seal YPM BC 005552; NBC 2579

Photograph by Klaus Wagensonner

We continue our series on the history of finance in Mesopotamia with an example of the earliest proto-cuneiform accounting “texts” dating to the late 4th millennium BCE. Pictured here is likely a receipt from Uruk or Jemdet Nasr, listing quantities of commodities and people associated with them.

more

The top left box (in the original orientation this was located in the top right corner) shows an ear of barley together with numerical notations. The metrological systems used are quite complex, and there were at least a dozen different systems depending on the commodity. For example, one system was used to count discreet objects such as humans and animals, and another one for counting grains. There are c. 60 individual numerical notations known, each given its own modern number e.g. N45 (the red large dot in the graphic).

In this text, the scribe recorded the amounts of barley in a capacity system that used its own bundling rules. The entry consists of a damaged vertical impression by a big round utensil (N45 in transliterations = red large dot) and seven smaller round impressions (7 N14 = blue smaller dots). The larger impression corresponds to ten of the smaller round impressions. Each of the smaller round impressions represent six slanted impressions by the smaller round utensil (N1 = orange notations).

The second entry of the text uses another set of numerical notations, this time another system for capacities, which is used probably for various kinds of emmer. The numerical notations look similar, although the scribe added two strokes to each sign. Despite this small modification, the bundling rules are the same as in the previous system. The signs in the other cases likely contain personal names and/or roles. One features the MUNUS sign, suggesting a woman’s name or title. Another entry contains a title also known from the List of Professions.

On the tablet's reverse the barley and emmer notations are totaled. The totals are damaged, but can easily be reconstructed.

See below video with Prof. Will Goetzmann, discussing this tablet.

YPM BC 026109; YBC 12314

Image by Klaus Wagensonner

YPM BC 026109; YBC 12314 Pavla Rosenstein

So far, we've looked at ancient Mesopotamian objects featuring transactions of movable commodities, for example livestock or grain. But this early stone object (sometimes referred to as a kudurru) appears to record a transaction of land - most likely involving an irrigated field(s).

more

The symbol for the irrigated field can be seen in the top right and consists of a straight line, with a striped rectangle to its right side, representing a canal and a number of smaller dykes used to water individual long and thin fields. The symbol is left of seven round impressions, which represent numerical notation outlining the size of the field.

This kudurru measures 78.0 mm × 78.0 mm × 25.0 mm and is unprovenanced, but likely comes from southern Mesopotamia in the early 3rd millennium BCE. Its proto-cuneiform script remains difficult to decipher fully.

The second image shows the hand copy, which, together with a tentative transliteration, is published in Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus by I. J. Gelb, P. Steinkeller, and R. M. Whiting Jr., published as OIP 104 (1989). The numbers associated with the field symbol suggest 2 bur'u (large circles) and 5 bùr (small circles), which comes to 450 IKU of land, which would be c. 160 hectares (just under 400 acres) in modern metrology. The large number of signs in the lower section of the tablet awaits a full interpretation, but likely records individuals associated with the transaction(s).

Prof. Will Goetzman will discuss the significance of this object in the history of finance in the video below

YPM BC 016868; YBC 02245

Photograph by Klaus Wagensonner

YPM BC 016868; YBC 2245 Pavla Rosenstein

During the Early Dynastic period (early to mid-3rd millennium BCE), we begin to see increasingly complex cuneiform texts now also including grammatical elements, which helped epigraphers conclude that these texts expressed the written language of Sumerian.

more

The period is characterized by a system of city-states in southern Mesopotamia (not dissimilar to ancient Greece), which shared a common culture, religious pantheon and written language. It is also when we can see the recorded use of compound interest for the first time.

Pictured is a clay vase (sometimes also interpreted as a mace) dating to c. 2400 BCE and commemorating the victory of the city of Lagash over the city of Umma. The two cities had a border dispute, which included access to irrigation water. Umma seized the border-land two generations prior to the inscription, and the victorious Lagash is now demanding reparations. The text reads, “the leader of Umma would exploit 1 guru of barley of the Nanshe and the barley of Ningursu as a loan. It bore interest, and 8.64 million guru accrued.” (translation after Van de Mieroop, 2005: 29). This is an impossibly high figure equivalent to c .45 billion hl of barley.

In his book, Money Changes Everything (2017) Will Goetzmann explains how the leader of Lagash, Entemena, “invokes the precedence of a barley loan to claim a customary rate of interest on grain of 33⅓ %". Goetzman also exaplains how the concept of compound interest is linked to expected reproductive growth of a herd of livestock - for example an owner of a herd would expect more cows and bulls to be returned to him than were loaned out several years earlier.

A later tablet from the Ur III period (AO 05499), for example, contains a model for the growth of a herd of livestock over a ten-year period, assuming no cow or bull dies, and each mating pair produces a male or a female calf each year.

Watch video below with Prof. Goetzmann discussing compound interest in more detail.

YPM BC 005474; NBC 02501

Photograph by Carl Kaufman

YPM BC 005474; NBC 02501 Pavla Rosenstein

Trade was a significant part of ancient Mesopotamian economy and archeological evidence points to extensive trade routes dating back to pre-history. By mid-3rd millennium, we can see detailed accounts of long-distance trade, featuring more than one polity.

more

Pictured above is an Early Dynastic (early to mid 3rd millennium) account of merchant trade in cuneiform. It is one of five such records from pre-Sargonic Lagash that document Sumerian trade with the island of Dilmun in present day Bahrain, about 800km south and likely involving travel along the river and the “lower sea” (today's Persian or Arabian Gulf).

The record shows that a merchant (dam-gàr) called DI-Utu brought to Dilmun 10 minas of refined silver, 300 minas of wool and commercial goods and brought back to Lagash 1350 minas of copper, 27.5 minas of tin and other commercial goods, handing them over to Baranamtarra, the wife of Lugalanda, the ruler (ensi) of Lagash. Baranamtarra then brought the goods to the storehouse, where Eniggal, the overseer (nu-bànda), made a balanced account, dated year 6 (of Lugalanda's reign).

Tin and copper were likely used for bronze-making, and although they were acquired in Dilmun, their origin is unknown. Any profit for the merchant, or whether he operated independently or within an official capacity of the city of Lagash also remains unknown. 1 mina is about 500g.

Prof. Will Goetzmann discusses this tablet in more detail in the video below.

YPM BC 025926; YBC 12130

Photograph by Klaus Wagensonner

YPM BC 025926; YBC 12130 Pavla Rosenstein

In the Old Assyrian period (early 2nd millennium BCE) a sophisticated trade network emerged in Mesopotamia, dominated by merchant families from Assur, which became an independent city state following the dissipation of the centralized polity usually referred to as the Third Dynasty of Ur.

more

Assyrian traders brought Babylonian and Assyrian textiles and tin to Anatolia in the west through c. 3-month long caravan routes in exchange for silver and other metals that were then brought back to Assur. The trade was managed through centers such as the city of Kanesh (today in Kultepe in modern Turkey).

While Kanesh was an Anatolian city, the excavated merchants’ quarter appears to have mainly been inhabited by Assyrian merchants and their families. Their homes contained over 23,000 of cuneiform records inscribed in Assyrian that recorded the merchants' business dealings, including a large number of letters between husbands and wives. The wives tended to stay in Assur and managed the business affairs there, including textile production and purchasing, while the husbands established a second home (often with a second wife) in Kanesh and managed transportation and sales, usually working with their fathers, brothers or sons.

The trade was regulated through taxation and other limitations known from a treaty concluded between the cities of Kanesh and Assur, but the trade itself seemed to be conducted entirely by private family-owned holdings, which also engaged in money lending. The above tablet is a short note recording the settlement of debt, which was witnessed by several parties, sealed, and placed within an envelope.

Prof. Will. Goetzmann will discuss the Old Assyrian network in more detail in the next video.

YPM BC 004875; NBC 1902

Photograph by Klaus Wagensonner

Women also had significant economic roles in the Old Babylonian period in southern Mesopotamia.

There was a particular class of elite woman called nadītum, from the verb nadûm, meaning to lay down or leave fallow. These “fallow” women were priestesses of the sun god Shamash, in particular in the city of Sippar and they were not expected to marry or have children.

YPM BC 019044; YBC 04980 Pavla Rosenstein

The tablet featured is an Old Babylonian mercantile partnership agreement with a list of witnesses: YPM BC 019511; YBC 05447 Pavla Rosenstein