Argentina: Emergency Liquidity Support Through Chinese Central Bank Swap Line and Qatari SDR Loan

Introduction

This summer, the Argentine central bank—the Banco Central de la República Argentina (BCRA)—has drawn on its central bank swap line with the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) for short-term liquidity support in the face of dwindling foreign reserves and external debt repayment deadlines. Unlike in past experiences, though, the BCRA has worked with the Ministry of Economy to use the renminbi (also known as yuan) proceeds to directly pay off debts maturing with the International Monetary Fund (IMF or the Fund), thereby using short-term monetary support to settle long-term fiscal debts. To support its position with the IMF and to avoid using dollars, Argentina also obtained a Special Drawing Rights (SDR)-denominated loan from Qatar to support a $2.7 billion payment to the Fund (and also received bridge funding from a Latin American development bank). Argentina continues to face macroeconomic headwinds and while the future is unknown (and includes some potentially radical measures), the episode represents an expanded role for an important crisis-fighting tool: central bank swap lines. The episode also highlights one way to deploy SDRs to support liquidity when needed without converting to hard currencies in a crisis.

Both of these foreign-currency liquidity tools are critical parts of the crisis-fighting toolkit. We have recently published a series of cases studies on central bank swap lines and a survey of swap lines’ use. Publications about the IMF’s liquidity operations are forthcoming.

Key Context: Central Bank Swap Lines and SDRs

Central Bank Swap Lines

For a brief primer on central bank swap lines, see this blog post explaining their purpose and operation. From the blog:

A central bank swap line is the central banker’s version of a currency swap, which is itself a loan in one currency collateralized by another currency. So, for example, let’s say you have euros but need dollars. I lend you $100 for a month, and you secure that loan with $100 worth of euros as collateral. At the end of the month, you give me my dollars back (plus interest) and I give you your euros back. (For those in the finance field, if this arrangement sounds like a repo, that’s because it is—they are typically structured as repurchase agreements). That’s a currency swap. So, a central bank swap is just that, but between two central banks.

In a recent publication of the Journal of Financial Crises, the Yale Program on Financial Stability (YPFS) team has written extensively about central bank swap lines and their importance in supporting foreign exchange liquidity during crises. Originally a foreign-exchange intervention tool, in the 21st century—and especially during and after the Global Financial Crisis—central banks began to use swap lines as crisis-fighting tools, satisfying foreign demand for U.S. dollars or other regionally important currencies (such as the Reserve Bank of India providing Indian rupees to Sri Lanka and Nepal, the European Central Bank providing euros to Sweden or Denmark, or the Swiss National Bank providing Swiss francs to the Eurozone). During the Global Financial Crisis, the U.S. (through the Federal Reserve) extended swap lines to 14 countries, which were used for a peak outstanding amount of $583 billion. Later, during the COVID-19 crisis, the U.S. again deployed its swap lines to 14 countries for a peak outstanding amount of $449 billion.

Special Drawing Rights

The Special Drawing Right (SDR) is an international reserve asset issued by the IMF whose value is determined against a basket of five global reserve currencies. Importantly, though, it is not itself a currency and cannot be used to pay for goods and services in the real economy. SDRs can be used to increase a member country’s reserves or to settle certain accounts with the IMF or another IMF member nation. The SDR is a claim on the freely usable currencies of IMF member nations (i.e., those in the SDR basket—currently, the dollar, pound sterling, yen, euro, and renminbi).

The IMF allocates SDRs to its member nations in proportion to their quota (share in the IMF) and most nations hold those SDRs to boost foreign reserves. The latest SDR allocation—made in 2021 during the COVID-19 crisis—was worth $650 billion. Through the use of Voluntary Trading Agreements (VTAs), IMF member nations can request to liquidate their SDRs for freely usable currencies with other IMF members (or some designated third parties, called Prescribed Holders) in a trade intermediated by the IMF. When the IMF allocates SDRs, the majority go to developed nations (since they have the largest shares in the IMF, or quotas). In order to get excess SDRs from developed nation balance sheets to those of low-income countries, rich nations can “recycle” SDRs by pledging them through IMF trusts (i.e., on-lending them through IMF lending programs). Recent proposals have included using SDRs to fund multilateral development banks with hybrid capital.

But there’s nothing stopping two countries from using SDRs in bilateral financial exchanges. While most transactions in SDRs are spot exchange transactions through VTAs (in other words, a real-time trade of SDRs from one country for a hard currency in another country), transactions can be structured as forwards, swaps, or loans. Therefore, theoretically, a country with a surplus of SDRs could provide SDRs to a counterparty through a loan, swap, or repurchase transaction. And while most transactions are done through VTAs, it’s also possible for two counterparties to transact bilaterally. (However, it’s quite rare: from September 2021 through August 2022, IMF members transacted SDR 17.3 billion through VTAs but only SDR 0.2 billion bilaterally.) Thus, while it’s not the norm, two countries could initiate an SDR-denominated and -cleared loan, swap, forward, or repurchase agreement bilaterally.

For a background of Global Financial Crisis- and COVID-era SDR interventions, see our blog post on the G20 SDR impasse in 2020.

Argentina Reaches for Chinese Swap Line, SDRs, in Bid to Support IMF Debts

PBOC Swap Line

For some context, China’s swap lines are somewhat unique. As we’ve discussed in our survey of central bank swap lines, while most swap lines are used to relieve funding pressures abroad for a home currency (for example, the Fed extending a swap line to the ECB in order to relieve dollar funding pressures in Europe), Chinese swap lines are often present in the absence of any renminbi funding pressures abroad. Political economist Daniel McDowell has argued that Beijing’s swap lines are a form of financial statecraft, with China using the PBOC liquidity lines to support renminbi internationalization. More recently, a group of scholars—Sebastian Horn, Brad Parks, Carmen Reinhart, and Christian Trebesch—have argued that China has employed its swap lines as a tool to act as an international lender of last resort, in effect challenging the IMF’s lending status in emerging markets.

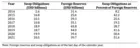

As we have detailed in our case study, Argentina has a history with the PBOC’s swap lines. The PBOC extended the first iteration of the swap line, for 70 billion renminbi (RMB), to the BCRA in 2009. By year-end 2022, China and Argentina had expanded the facility to RMB 130 billion, including the addition of two supplementary facilities. By 2014, the BCRA had made draws on the swap line, and rumors spread that it had used renminbi proceeds to buy dollars in the foreign exchange market. In 2015, the BCRA and PBOC formalized a renminbi-for-dollar leg, expanding the swap arrangement with a second-step swap with the PBOC (in other words, the BCRA would swap pesos for renminbi, and then renminbi for dollars).

Not only did Argentina have access to a large Chinese swap facility, but it has used it extensively. Between 2014 and 2021, Argentina drew on the PBOC swap line every year.

Since last year, Argentina has worked to expand access to the Chinese swap line, and in November had success: Beijing agreed to make another RMB 35 billion ($5 billion) freely available for Buenos Aires to use for non-trade purposes. In January, the BCRA and PBOC activated the line for Argentina to use the proceeds to defend its currency.

In the spring of this year, the macroeconomic situation in Argentina deteriorated further as currency depreciation continued amidst the backdrop of a drought that shocked Argentina’s exports. Meanwhile, large IMF debt repayments loomed in the summer.

On June 2nd, Argentina and China renewed the swap line and doubled the RMB 35 billion ($5 billion) freely available amount to RMB 70 billion ($10 billion). At that point, the swap line stood at RMB 130 billion, of which RMB 70 billion was freely usable in two RMB 35 billion tranches—the first for commercial exchanges and the second for “any type of financial operation.” To access the second freely available tranche, the first tranche should first be exhausted.

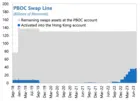

Four weeks later, Argentina announced that it had, for the first time ever, used a $1 billion draw (roughly RMB 7.2 billion) on the PBOC swap line (along with $1.7 billion of SDRs) to repay IMF debts. Then, on August 1st, Argentina confirmed that it would use $1.7 billion from the second tranche of its PBOC swap line (alongside a $1 billion bridge loan from a Latin American development bank) to again make a payment to the IMF. Two days later, Argentina and Qatar finalized a $775 million loan in SDRs to repay the IMF.

The mechanics of the swap drawing were the subject of discussion at the IMF. In its August 25 review, the IMF called the PBOC swap drawing for the IMF repayment a “bridge loan,” in contrast to previous draws, which it called swap line activations or uses. Further, as mentioned above, Argentina said it would use $1.7 billion (roughly RMB 12.4 billion) from its second tranche of the freely available portion of the swap line but, per the IMF, it had only used roughly $3.8 billion (roughly RMB 27.7 billion) of the first tranche (these funds were used for imports, paying foreign bondholders, and IMF repayments in June), which should have been exhausted before the second tranche could be activated. The IMF on the topic: “Activation of a second tranche for an equivalent amount as the first tranche remains a subject of discussion.” According to Reuters reporter Jorgelina do Rosario, the PBOC chose to activate the $1.7 billion from the second tranche as a “bridge loan” specifically for that purpose and for nothing else. Administratively, China and Argentina agreed on the swap draw and then a Chinese bank paid the $1.7 billion directly to the IMF in renminbi. While initially some expressed concerns that the IMF would not accept payment in renminbi, the IMF reiterated that the renminbi is one of five freely usable currencies through which IMF members can settle payments with the IMF. According to do Rosario, Argentina quickly paid that “bridge loan” draw back with the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) disbursement funds it received from the IMF on or around August 23.

As we have outlined in our survey of central bank swap lines, swap lines are often used to calm funding pressures in foreign currency markets abroad, but can at times be used (particularly in the case of Chinese swaps) as a quasi-fiscal tool to, in effect, bail out central banks facing maturing debt or a currency crisis. Recent research has shown that China uses its swap lines to provide relief to countries indebted to Beijing through infrastructure debt accumulated as a result of its flagship Belt and Road Initiative. The recent move by Buenos Aires to utilize the short-term crisis-management tool (which the BCRA itself classifies as 0–3-month debt) to finance much longer-term IMF debt marks a milestone in the extent to which nations have used central bank swap lines to finance fiscal debts.

Qatari SDR Loan

On August 3, Argentina and Qatar finalized a $775 million loan in SDRs from Qatar to Argentina to repay the IMF. The loan comes due on September 6, 2023. According to the agreement (§7.2), Argentina would repay Qatar with the proceeds it derives from the IMF’s fifth and sixth reviews of its EFF arrangement. Moreover, Argentina instructed the IMF to automatically draft the principal and accrued interest payment from its EFF disbursement directly to Qatar, such that those funds never actually reached Argentina’s account. On August 23, the IMF concluded its combined fifth and sixth reviews under Argentina’s EFF arrangement, enabling an immediate $7.5 billion disbursement. Pursuant to its loan agreement with Qatar, Buenos Aires used the proceeds from this disbursement to repay the SDR loan.

Lending like this—from sovereign to sovereign in order to provide eleventh-hour bridge financing for IMF repayments—is not new. The U.S. has used the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) to lend to sovereigns, often in very short (a few days or even one day) loans to bridge borrowers for IMF repayments.

The Qatari SDR-denominated loan also represents the first credit operation between the two countries. Similar to the sometimes-opaque nature of swap lines, the negotiations surrounding the Qatari loan were completed “in absolute secrecy.”

Timeline: China, Argentina, and the IMF

Mar. 18, 2022 - Argentinian Congress approves restructuring of 2018-origin Standby Arrangement debt with new EFF.

Mar. 25, 2022 - IMF approves EFF for Argentina for $44 billion.

Nov. 15, 2022 - China expands swap line by making RMB 35 billion ($5 billion) freely accessible to Argentina in special FX facility.

Dec. 31, 2022 - BCRA has $18.7 billion—or 42% of its foreign reserves—in PBOC swap line obligations, classified as 0–3 month liabilities.

Jan. 8, 2023 - The BCRA and PBOC confirm a “special activation” of their swap line.

May 11, 2023 - The BCRA has used all RMB 35 billion of its freely available portion of the swap line to intervene in the foreign exchange market.

June 2, 2023 - Argentina and China renew swap line and expand the RMB 35 billion ($5 billion) freely available amount to RMB 70 billion ($10 billion).

June 30, 2023 - For the first time ever, Argentina uses RMB 7.2 billion ($1 billion) from the PBOC swap line, along with $1.7 billion of SDRs, to repay the IMF.

July 31, 2023 - Argentina's Economy Minister Sergio Massa says Argentina will not use “a single dollar” from its reserves to make a $2.7 billion payment to the IMF.

Aug. 1, 2023 - Argentina confirms that it will use $1.7 billion from the second tranche of its PBOC swap line to again make a payment to the IMF. Argentina also confirms a $1 billion bridge loan from the Andean Development Corporation.

Aug. 3, 2023 - Argentina and Qatar finalize a $775 million loan in SDRs from Qatar to Argentina to repay the IMF.

Aug. 4, 2023 - Argentina reaches agreement with Chinese bank for the IMF bridge loan financed by the standing swap arrangement.

Aug. 13, 2023 - Javier Milei—libertarian economist, supporter of dollarization, and critic of the central bank’s existence—wins Argentina’s presidential primary race in an upset.

Aug. 14, 2023 - BCRA devalues the peso 18% against the dollar and raises benchmark rate from 97% to 118%.

Aug. 23, 2023 - IMF completes its combined fifth and sixth reviews of Argentina’s EFF Arrangement, enabling $7.5 billion disbursement. Argentina plans to use the disbursement to repay PBOC swap draw.

Mixed Reactions

Carnegie Endowment scholar Michael Pettis said that Argentina’s drawing on the swap line was risky for China:

If Argentina recovers and regains full access to international capital markets, this will seem to have been a smart move to increase international use of the [renminbi]. But if Argentina continues to struggle with its external debt burden, the use by Buenos Aires of [renminbi] borrowing to service [dollar] debt will only increase the Chinese share of the country's total debt burden, while only temporarily increasing the international use of [renminbi].

Argentinean Economy Minister Sergio Massa said that the challenge for Argentina was to “continue to take care of the [foreign currency] reserves” and that he hoped to bring “peace of mind” to Argentineans that the country wouldn’t use its dollars.

Publication Al Jazeera called the swap line a “yuan lifeline” and a “sign of brinksmanship” between Washington and Beijing.

Matthew Mingey, senior analyst at Rhodium Group, said that China’s aim isn’t to replace the IMF:

When China has allowed these swap lines to be tapped, in many cases it's to unlock an IMF bailout or ensure an IMF program stays on track . . . This is not free money, and even where the PBOC has a large facility agreement in place, these swap lines often come with drawdown conditions.

Mark Sobel, a former senior U.S. Treasury official, said that the PBOC was acting as a bridge loan provider and that “China has every incentive to tightly manage Argentine drawings under the swap lines as the risks are very high.”

New Milestones

China and Argentina have a history of cooperation in using renminbi-denominated swap lines to support the BCRA. This summer’s actions indicate a further expanded role of central bank swap line use as the tool evolves from what was initially a foreign-exchange intervention tool to a crisis-management tool to an expanded international loan facility with increasingly broad applications. Meanwhile, the Qatari SDR-denominated loan represents the first credit agreement between the two countries and a comparatively rare bilateral non-spot SDR transaction, as Doha provides bridge financing in ways similar to historical Treasury ESF loans. Both efforts were communicated as ways to protect Argentina’s precious dollars. That calculus may change if Mr. Milei wins the presidential election and replaces the peso with the dollar. For now, this recent episode has shown that financial stability tools can be repurposed to fit the next crisis.