Weekly Fed Report Still Drives Discount Window Stigma

As banking regulators work to destigmatize the Federal Reserve’s discount window—and fervently so since the 2023 banking crisis—they’ve pointed to several potentially fruitful policy routes. These have included supervisory improvements, regulatory changes, and operational enhancements on both the banks’ and the Fed’s sides. Left off the menu so far have been changes to the Fed’s weekly publications that reveal up-to-date discount window borrowing data by regional geography. While the Fed attempted to address this issue in 2020, these weekly publications still risk “outing” the discount window borrowing of a large bank based in a particular region. This risk of the market discovering this activity stigmatizes discount window use, undermining policymakers’ other destigmatization efforts to encourage its use when appropriate.

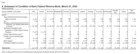

Each of the Fed’s 12 regional Reserve Banks operates its own discount window for the banks headquartered in its region. When the Fed publishes the so-called H.4.1—a weekly snapshot of its balance sheet—the Fed provides a breakdown of assets and liabilities by each regional Reserve Bank. Each week, the Fed releases the H.4.1 on Thursday, disclosing its balance sheet as of the end of that Wednesday. The report currently displays the regional breakdown of assets across Reserve Bank like this:

Even prior to the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010—which required the Fed to disclose on a two-year lag transaction-level discount window data, including the borrower’s name—these regional disclosures drove discount window stigma for larger banks. This was because market participants knew where banks were headquartered—and thus which Federal Reserve district they were in. If the market was particularly worried about, say, Wachovia—the Charlotte, North Carolina-based bank that nearly failed in 2008—a suddenly large balance of discount window loans on the Richmond Fed balance sheet might have triggered further concern.

In 2020, the Fed changed the way it reported regional Reserve Bank balance sheets in an attempt to reduce that stigma. While it may have been directionally helpful in that moment, it did not solve the stigma problem caused by the regional disclosures. At a Brookings Institution panel last month, Bill Demchak—CEO of the $550-billion PNC, the US’s sixth-largest bank—said (emphasis added throughout):

The day you hit [the discount window] for anything other than a test, you effectively have told the world you’ve failed. And investors look at that number; it's disclosed because it's by district.

PNC is based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; investors would be closely watching the Cleveland Fed data.

What the 2020 change fixed—and didn’t

At the outset of Fed’s pandemic response in 2020, the Fed changed its weekly balance sheet reporting to try to mask the regional discount window data. Here is how the regional breakdown table looked before and after the change (red annotations added throughout):

While still displaying a regional breakdown of assets, the Fed rolled each Reserve Bank’s “Loans” category into an aggregated line item inclusive of other assets. On March 19, 2020, the Fed’s H.4.1 release included an announcement that said, in part:

Modifications include the consolidation of amounts previously reported as "Loans," which includes discount window borrowing, into the line "Securities, unamortized premiums and discounts, repurchase agreements, and loans." This modification supports the Federal Reserve's goal, expressed in its statement on March 15, 2020, of encouraging depository institutions to use the discount window to help meet demands for credit from households and businesses, including needs related to the spread of the coronavirus.

The 2020 modification of the weekly balance sheet disclosures was at its most helpful in encouraging discount window use at a time like the pandemic, when the Fed was also rapidly growing its balance sheet with large-scale open market operations. This meant the loans could disappear into a line item that now also included the regional allocations of the Fed’s purchases and repos of Treasuries and agencies (henceforth, “domestic SOMA assets”).

The 2020 modification is at its least helpful, however, when the Fed’s balance sheet assets are otherwise relatively stable. In such a case, a sizable regional increase in the newly combined "Securities, unamortized premiums and discounts, repurchase agreements, and loans" item—i.e., domestic SOMA assets plus discount window loans—will quickly reveal any sizable regional discount window loan. This is because discount window loans are assigned on the balance sheet to the actual lending Reserve Bank, and domestic SOMA assets wouldn’t be responsible for the increase given the absence of open market operations.

In this regard, the timing of the 2023 banking crisis was less optimal for leveraging the 2020 modification. At the time of the crisis onset, the Fed was (and still is) in the process of quantitative tightening (QT)—allowing some securities to run off its portfolio. So, when the weekly Fed balance sheet disclosure revealed substantial asset increases at some regional Reserve Banks, markets could comfortably blame regional discount window loans—despite the loans being lumped in with regional allocations of securities holdings.

For instance, following the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank, the Wall Street Journal published an article breaking down the regional increases, with this picture atop the article:

Fortunately, markets could take some comfort that the large increases were in the districts of the failed banks, with SVB in the San Francisco district and Signature in the New York district (if also putting some further pressure on West Coast banks, given the total San Francisco region increase could not be explained by SVB and First Republic[i]). Yet, this kind of story and chart also reveals some unsettling counterfactuals.

For instance, one bank that temporarily faced substantial market pressure in the aftermath of SVB’s failure was the then-$550-billion Charles Schwab. Ultimately, the bank weathered the crisis, and pressure eased. However, if the Westlake, Texas-based Schwab had used the discount window to help withstand the market fallout from the SVB failure, the above chart would have shown a substantial asset increase at the Dallas Fed. This likely would have precipitated further pressure on Schwab—working at cross-purposes with the discount window’s aim of limiting contagion.

Other Cases: Tougher, But Still Doable

It should also be noted that even a massive QE operation need not mask the discount window data from analysts. Assets acquired in monetary policy operations—which are conducted out of the New York Fed—are allocated across the regional Reserve Banks’ balance sheets formulaically, and thus can be approximated and backed out of the aggregate data. This allocation of domestic SOMA assets includes all the assets in the newly aggregated "Securities, unamortized premiums and discounts, repurchase agreements, and loans" item on the Fed balance sheet except for the “loans” balance, which covers the discount window.

Every April, the Fed resets the regional percentage allocations of domestic SOMA assets, which then apply for a year. While these percentages are not disclosed until the following year’s financial statements (shortly before being reset again), they can be estimated by looking at the allocated share to each bank in a week where discount window activity is minimal, or comparing week-over-week allocations of any asset increase or decrease in two weeks where discount window activity was little changed.

Then, when allocations deviate meaningfully from those estimates, and the aggregate balance sheet shows rising discount window activity, analysts can identify the Fed district(s) associated with that borrowing.

Undoing the Fed’s Aggregation in 2020

Take, for instance, an analyst wanting to deduce regional discount window borrowing after the Fed took away the regional breakdown in the March 19, 2020 weekly balance sheet disclosure. (Due to Dodd-Frank Act disclosure requirements to disclose within two years, we can now check our work here with transaction-level data the Fed disclosed in 2022.)

The January 23, 2020 release of the balance sheet shows zero discount window activity as of January 22:

This means the regional percentage allocations can be quickly backed out by dividing each district’s domestic SOMA assets amount by the total[ii]:

Now, take the March 19, 2020 balance sheet—when the Fed began rolling each regional Reserve Bank’s discount window activity into the aggregated line item:

It still disclosed aggregate discount window borrowing elsewhere in the H.4.1: Such borrowing stood at $28.224 billion as of March 18, 2020:

Deducting this aggregate discount window amount from the “Total” amount in the first column of the regional breakdown table (Figure 7) provides the total for everything but the discount window.

Taking that new amount—representing just the domestic SOMA assets—and allocating it by the percentages calculated from the January balance sheet, it was then visible how much each region’s actual total for the newly aggregated line item deviated from what would be expected based on its allocation of monetary policy assets alone. This deviation represented implied discount window use. Transaction-level data released in 2022 can now verify how accurate this process would have been in real-time.

As the table below shows, each district was estimated correctly within a million dollars (with slight the exception of New York, which seems to be housing an additional approximately $150 million of discount window loans that appear in the transaction data but did not appear in the real-time H.4.1 disclosure, hence the slight discrepancy between the transaction data and H.4.1 totals):

Thus, despite the Fed no longer publishing the “Loans” line item, analysts were still able to track regional discount window activity and look for suspected borrowing from large banks located in specific geographies.

Notably, though, the Fed’s 2020 aggregation effort to mask regional borrowing also benefitted from introducing the Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility (PPPLF), which began operation in April 2020. The PPPLF was one of several so-called Section 13(3) emergency facilities implemented by the Fed in response to the pandemic. However, in contrast to the other programs, the PPPLF was run out of all 12 Reserve Banks’ discount windows. This program, which peaked at over $90 billion, thus muddied the ability to read calculated regional loan amounts purely as discount window loans.

The PPPLF was not stigmatized as it was effectively a funding-for-lending operation, providing banks liquidity for their participation in making PPP loans—a pandemic-era emergency program run by the Small Business Administration that provided government-guaranteed small business loans. (The PPPLF is technically still in runoff mode—approximately $3 billion left to run off—slightly distorting an analyst’s view of the regional allocations, though the effect is approaching zero.) The mostly unknown regional dispersion of PPPLF loans combined with the lack of stigma reduced the usefulness of the regional Fed lending data for determining actual discount window borrowing; PPPLF lending could not be distinguished from discount window lending at the regional level.

In the 2023 crisis, the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) was similarly run out of each Reserve Bank’s discount window. In contrast to the PPPLF, however, it’s not clear the market viewed the BTFP with much less stigma than discount window borrowing, particularly in the acute phase of the crisis. For instance, BTFP borrowing was grouped into the Wall Street Journal chart above. Thus, an analyst’s calculations would’ve estimated the sum of discount window and BTFP borrowing—i.e., there was no non-stigmatized regional lending through which discount window lending could be rinsed.

Where does that leave us?

Greater aggregation, in the spirit of the 2020 changes, could help. As one can see in the disclosure’s current form (presented again below), there are several other line items affecting each regional Reserve Bank’s assets:

These other items are driven by district-level conditions or are otherwise allocated by different formulas than the domestic SOMA assets; further aggregation—even, say, simply disclosing each region’s total assets without any specific line items—could thus help achieve what the Fed sought to in 2020.

Greater discount window usage in “normal” times would itself help at the margin by muddying the ability to estimate regional allocations of domestic SOMA assets. This partial solution is something of a catch-22 given that the stigma caused by these disclosures limits use of the window in the first place, but more substantial use by small banks or increased discount window operational tests (whether mandatory or voluntary) could help.[iii]

After the financial crisis, the Congress demanded greater transparency on Fed lending. In a tradeoff with not wanting to cause discount window stigma, it settled on mandating the Fed disclose loan-level data only after a two-year lag.

The Fed’s status quo, however, undermines that balance; larger banks’ use of the discount window risks public disclosure at a weekly cadence.

[i] After a back-of-the-envelope accounting, the article concludes: “The upshot is that almost all of the remaining borrowing—potentially less than $40 billion—last week would have come from other banks in the west.”

[ii] The Fed was still displaying the separate “Loans” line item at the time, but the process shown here is ignoring that to show how the calculation could work even without that line item.

[iii] Leveraging all 12 regions for non-stigmatized lending facilities, such as the PPPLF, can also be marginally helpful. However, relying on 13(3) invocation is not consistent with standalone efforts to destigmatize the discount window in all environments (and thus help prevent the need for using the 13(3) emergency authority). Moreover, the PPPLF was non-stigmatized due to the nature of the pandemic and the fiscal guarantees of the lending; as we saw with the BTFP, broad-based emergency lending facilities can also come with discount-window-like stigma. This solution would thus require a more novel use of Fed’s non-emergency lending authorities—if not a statutory change.