Part III of Crisis in Lebanon: Public Protests, COVID-19 Crisis, and International Support

In this last blogpost of the Lebanon series, we explore how the COVID-19 has impacted the country while it was already undergoing a severe economic and financial crisis. With the limited fiscal space and lack of resources, the most vulnerable Lebanese people are at risk. Aside from the potential IMF support, which is still under discussion, the government could seek to unlock the pledged CEDRE aid or ask for bilateral support. In any case, the road to recovery will be long and winding.

Also read “Part I: Current Situation” and “Part II: The Buildup of the Crisis”.

*The author would like to thank Rana Alayli for research support and comments.

The start of the crumble in late 2019

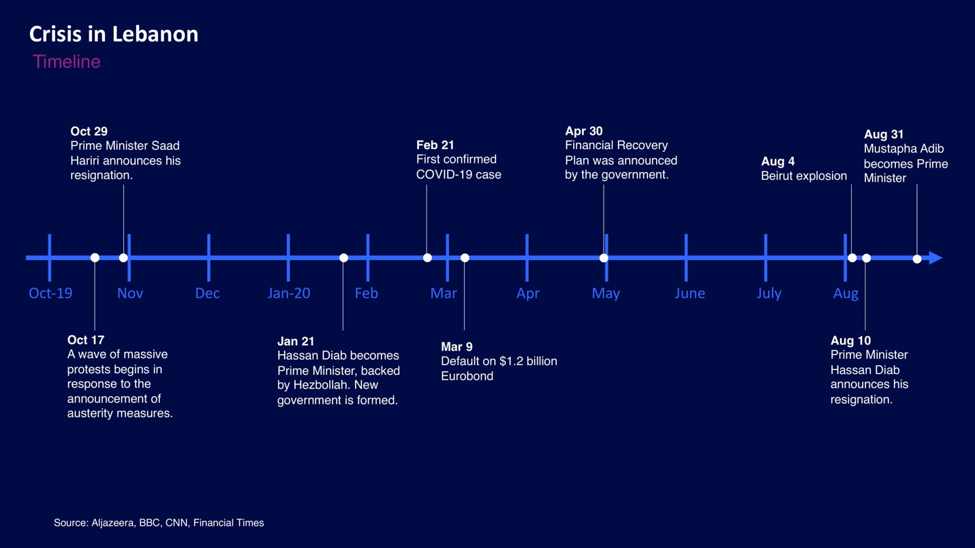

In October 2019, an austerity plan based on proposed taxes on tobacco, petrol, and voice calls via WhatsApp ignited a mass protest against corruption, bad governance, and inequalities. In a speech on October 21, Prime Minister Hariri promised economic and fiscal reforms, including halving government officials’ salaries. However, Hariri resigned only eight days later, leaving the government leaderless for months. In late January 2020, the new government was finally formed. Hassan Diab, a professor and former education minister, was named prime minister. His appointment was backed by Hezbollah (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The public has vented its frustration not only toward the government but also toward banks and business elites. Since the outbreak of the protest, most banks either shut down or limited dollar cash withdrawals by their depositors, an unofficial capital control. Meanwhile, according to Alain Bifani, a former top finance civil servant, banks themselves successfully circumvented the de-facto capital control and “smuggled” approximately $6 billion outside the country. The social unrest led to the further flight of deposits and shortage of the USD, exacerbating the ongoing financial crisis.

COVID-19 Crisis

The COVID-19 crisis came on top of an economic, financial, and political crisis that was already underway in Lebanon. The government was relatively swift in responding to the crisis; on January 31, the newly appointed government established a National Committee for Covid-19, issuing stay-at-home orders in March to contain the pandemic. The first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the country on February 21.

In early April, the Lebanese government announced that it would distribute LBP400,000 (approximately $265 at the official fixed exchange rate) to the poorest. It further pledged LBP 75 billion for sanitary and nutritional assistance. Local media reported that LBP 18 billion out of the 75 billion would be distributed in the form of food and health goods. However, there has been little information on distribution and it is uncertain whether these aids have materialized.

Infection numbers started to surge in mid-July. The government is re-imposing the once-lifted lockdown. The increase was particularly significant after the explosion in Beirut (Figure 2). As of August 20, new confirmed cases (seven-day rolling average) have exceed 400. According to the UNOCHA, the explosion damaged six hospitals and 20 health clinics, facilities much needed for the most vulnerable.

Figure 2

The negative impact of the economic and financial crisis on Lebanon’s health infrastructure had been apparent prior to the outbreak of COVID-19. In December 2019, Human Rights Watch reported that the Ministry of Finance had been failing to pay US$1.3 billion in dues to private hospitals, which account for 82 percent of Lebanon’s healthcare capacity. Furthermore, Lebanon imports 100 percent of its medical supplies; hospitals receive their payments in LBP and purchase medical equipment in USD. As the LBP plunges in value, hospitals and doctors struggle to secure essential medical supplies. The financial constraint on the healthcare industry is only exacerbating as the COVID-19 spreads. Hospitals are laying off staff, and nearly a third of Lebanon’s 15,000 physicians aim to or already have migrated.

The chronic electricity shortage is also hindering the delivery of essential services. Most recently, widespread power cuts lasting longer than 20 hours forced hospitals to restrict their capacity as they rely on generators and fuels to sustain the essential care units.

On July 20, Hamad Hassan, the Minister of Health, said that the country is sliding toward a “critical stage,” referring to the spike in positive cases. While the country reopened the economy by early July, the government had to reintroduce lockdown on August 3 due to the rise in cases.

International Support

The lack of fiscal space and political impasse have made it difficult for the government to provide support to the most vulnerable people in Lebanon. The proposed IMF support of about $10 billion could ease some of the pressure; however, the progress of negotiations has been sluggish, and it is uncertain when the government and the IMF could reach to an agreement. Furthermore, structural reforms requested by the IMF will be painful and would be subject to demur by incumbent elites.

Further international support could come from other multinational organizations, such as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Lebanon could also unlock the $10.8 billion in aid that France and 47 other countries and institutions pledged in 2018. In April 2018, France, led by President Emmanuel Macron, hosted CEDRE (Conférence économique pour le développement, par les réformes et avec les entreprises), an international conference aimed to support Lebanon’s development and reforms. At the conference, the Lebanese government presented its Capital Investment Program focusing on infrastructure. The CEDRE participants agreed to support the Program conditional on reforms, including the reform of Electricité du Liban (EdL), the dominant state-owned electricity company that is known to be failing (see Part II for more details). The pledged aid included $10.2 billion in loans and $860 million in grants. The loans are reported to consist of $4 billion from the World Bank; $1.35 billion from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; and $1 billion via a credit line from Saudi Arabia, which was a renewal of a previously pledged loan. Pierre Duquesne, a French diplomat assigned by President Macron to monitor the process, notes that those required reforms are “simple” and “achievable” in the short term. However, to date, Lebanon has failed to implement the promised reforms. Thus, CEDRE support has not come through.

Bilateral support is another option included in the recovery plan that the government published in April in preparation for IMF negotiations. According to the plan, the government envisages a deal “similar to what Egypt unsuccessfully tried to do back in 2014 with Saudi Arabia and the UAE to avoid the currency devaluation the IMF was asking for as a precondition to its intervention.” The recovery plan hints that such a deal is less likely than that earlier proposal to require austere reforms; it said that the “immediate visible costs to the Lebanese people would be smaller, with only a modest fiscal consolidation.” The report also acknowledged that it would leave the burden of accumulated losses to the next generation.

Any of these bilateral deals, if they happen, would need to be sizable. Considering that all countries are suffering from fiscal challenges caused by COVID-19, they may not be forthcoming. Lebanon also faces difficulties in securing international aid due to the geopolitical tensions between Hezbollah and international communities. For instance, US officials are said to be concerned that any humanitarian aid for Lebanon could be routed to Hezbollah; this makes the US hesitant to support aid beyond emergency food and medical supplies.

Meanwhile, the government and Hezbollah may seek help from China. On June 16, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah hinted that Lebanon should welcome Chinese investments in key infrastructure projects, while blaming the US for the shortage in foreign exchange. According to the Washington Post, China has offered to help Lebanon by building power stations and supporting other infrastructure through Chinese state-owned companies. It is still uncertain whether the Chinese aid will materialize.

Debt restructuring and reform are likely to take a long and winding journey for Lebanon and most likely will require external support.