Despite Stated Exclusion, the Fed Is Buying Bank Debt

The Federal Reserve has said it won’t directly buy bonds issued by banks as part of its COVID financial rescue facilities. But a close review of its holdings reveals that by buying exchange traded funds, it has indirectly bought $2 billion of bank bonds—over 15% of its total corporate bond holdings.

The Fed unveiled two facilities to purchase corporate bonds on the primary and secondary markets in March, as the growing pandemic roiled financial markets, causing selloffs across risk assets and impeding the financial intermediation of dealers and lenders.

The two facilities are the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) and Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF). The Treasury originally capitalized them with existing funds in its Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF). It later replaced those funds with new, specific ESF funds allocated by the CARES Act.

The Fed designed the PMCCF and SMCCF to leverage the capital provided for loss protection by the new Treasury funds into up to $500 billion of new corporate bond purchases and $250 billion of secondary market corporate bond purchases. For a full description of the PMCCF and SMCCF, see here and here.

While, to date, no firms have issued bonds to the PMCCF, the SMCCF has purchased securities on the open market. It has bought investment-grade and high-yield corporate bond exchange-traded funds (ETFs) since May, and a portfolio of individual-name corporate bonds that tracks a broad market index since June. As of the Fed’s September 8 report of its August 31 holdings, the SMCCF holds over $12 billion of corporate bonds and corporate bond ETFs. It has considerably slowed its purchases given the recent calm in bond markets.

Buying Bank Bonds through ETFs

When the Fed laid out its terms for the purchase of corporate bonds, it said it would only buy the bond of “an issuer that is not an insured depository institution, depository institution holding company, or subsidiary of a depository institution holding company.” Following that policy, none of the Fed’s purchases of individual-name bonds in the secondary market have been bank bonds.

However, the Fed said that ETFs it purchased wouldn’t be held to the same criteria as individual bonds. According to the Fed’s initial terms for the SMCCF: “In some cases...ETFs may include underlying bonds that have a remaining maturity longer than 5 years at the time of purchase, or include underlying bonds that would otherwise be ineligible for purchase by the SMCCF.”

This made it clear that the Fed might buy ETFs that held bank debt. Indeed, banks make up 21% of the investment-grade credit market, based on the industry-standard ICE/BofA corporate credit indexes. It should be expected that ETFs designed to broadly track that market would include some bank debt.

However, given that it was excluding bank debt from its individual corporate bond purchases, the Fed also explicitly said that it would consider “the amount of debt held in depository institutions” in an ETF before making a purchase decision. Yet, when looking at outcomes, it’s not clear that this restriction has been binding.

Unlike with its individual-name bond holdings, the Fed does not provide a breakdown of the industry allocation of its ETF holdings. However, it is possible to deduce that allocation by reviewing the public disclosures that ETF managers provide.

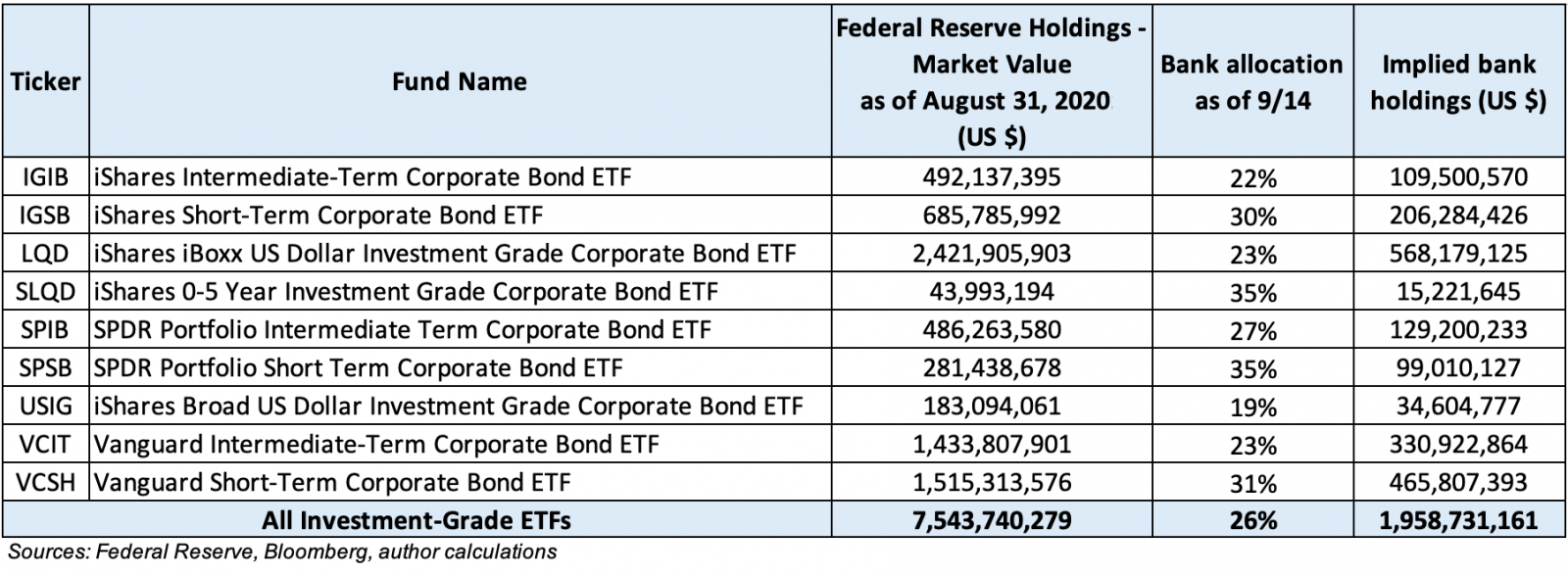

Based on August 31 data, the Fed held just over $7.5 billion of investment-grade ETFs. Those ETFs, in turn, held $7.5 billion in bonds, of which about $2 billion, or 26%, were bank bonds. (There is also a slim percentage of bank holdings—less than $20 million—in the Fed’s holdings of high-yield ETFs. It is uncommon for banks to be rated below investment-grade: banks make up just 2% of the high-yield bond market, per ICE/BofA.)

Based on a review of public filings, eight of the nine investment-grade ETFs the Fed has bought have a higher allocation to banks than the market benchmark of 21%. Three of the nine have bank weightings exceeding 30%, and two have weightings of 35%.

The result is that, despite the self-imposed restriction against buying individual bank bonds, over 26% of the SMCCF’s ETF holdings and 15% of its total holdings are claims on bank bonds.

Unprecedented?

The federal government has borne the credit risk of term bank bonds before. In 2008, during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) rolled out its Debt Guarantee Program (DGP). For participating banks, the FDIC extended the full faith and credit of the U.S. government to guarantee privately issued bank debt in exchange for a fee—akin to an insurance premium. The program peaked at $350 billion of issuance, collecting $10.4 billion in premiums and paying out $153 million to cover defaults.

However, following post-crisis legislative reforms, such guarantees now require explicit Congressional approval, in addition to the pre-existing requirements for approval from the Fed, FDIC, and Treasury in consultation with the President.

Via these ETF purchases, the market for bank debt is receiving federal support, if on a much smaller scale. The Fed has said that if financial market volatility picks up again during this pandemic, both ETF purchases and individual bond purchases would be scaled back up. Under such circumstances, the Fed’s holdings of bank bonds would be expected to grow as well.

Yet, with the SMCCF currently capped at $250 billion (and lower to the extent it includes high-yield assets, which it’s leveraging at a lower ratio) and bank bonds representing just a fraction of holdings, the total amount of federally-supported bank debt would remain a fraction of the peak outstanding DGP debt during the GFC, and the credit risk-bearing would not be as targeted. That is assuming no major expansion of the facility, shift to buying bank-only ETFs, or some similar repurposing takes place.