Part I of Crisis in Lebanon: Economic “Free Fall,” IMF Negotiations, and Beirut Explosion

In the first blogpost in a series, we introduce the ongoing crisis in Lebanon. On March 9, the country defaulted on its sovereign debt for the first time in its history. At the time, it had one of the highest ratios of debt to GDP in the world. While the government was in the midst of negotiations with IMF for a support program, on August 4, the country’s capital faced a catastrophic explosion caused by neglected ammonium nitrate.

Also read “Part II: The buildup of crisis ” and “Part III: The Future of Lebanon ”.

Current situation

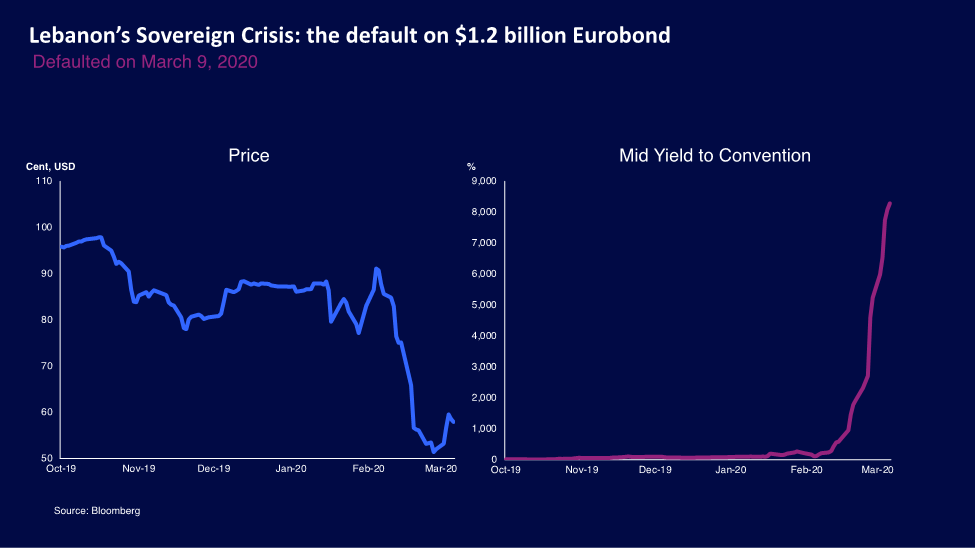

On March 9, Lebanon missed a payment on a $1.2 billion Eurobond. It was Lebanon’s first sovereign default in its history. The market had been wary of the solvency. The price fee to 57 cents on the eve of default while the yield on the bond surpassing 1,000% (Figure 1). The government subsequently announced it would discontinue all principal and interest payments on foreign currency-denominated Eurobonds.

Figure 1

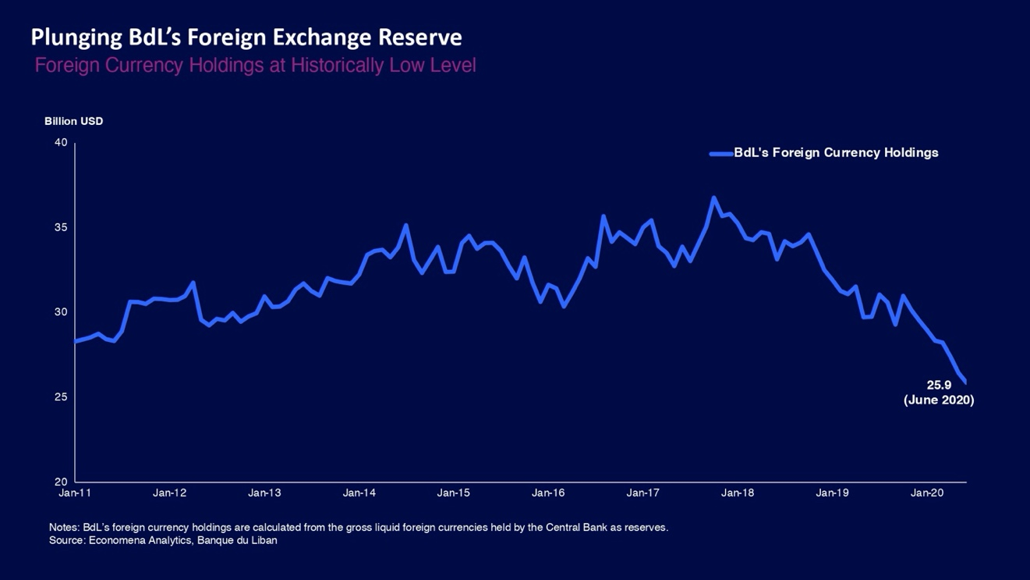

he government also disclosed that the foreign exchange reserves held by Banque du Liban (BdL), the Lebanese central bank, were experiencing a “rapid downward trend.” The $29 billion foreign exchange reserves as of January 2020 were too low to sustain the Lebanese economy facing immense debt (Figure 2). The government claimed that $22 billion out of the $29 billion foreign exchange reserves consisted of liquid assets. Meanwhile, given the opacity of the BdL’s foreign exchange disclosure, some question the actual size of liquid foreign-currency assets.

Figure 2

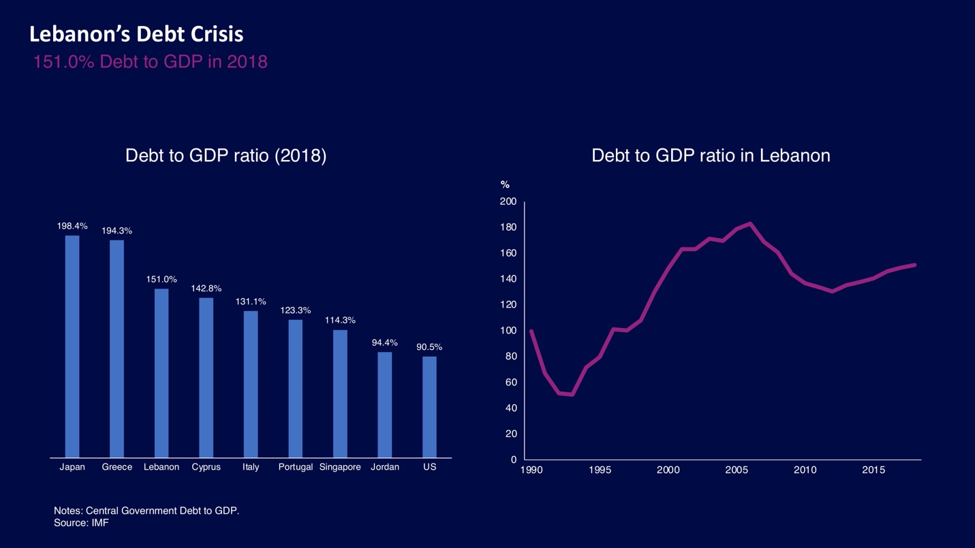

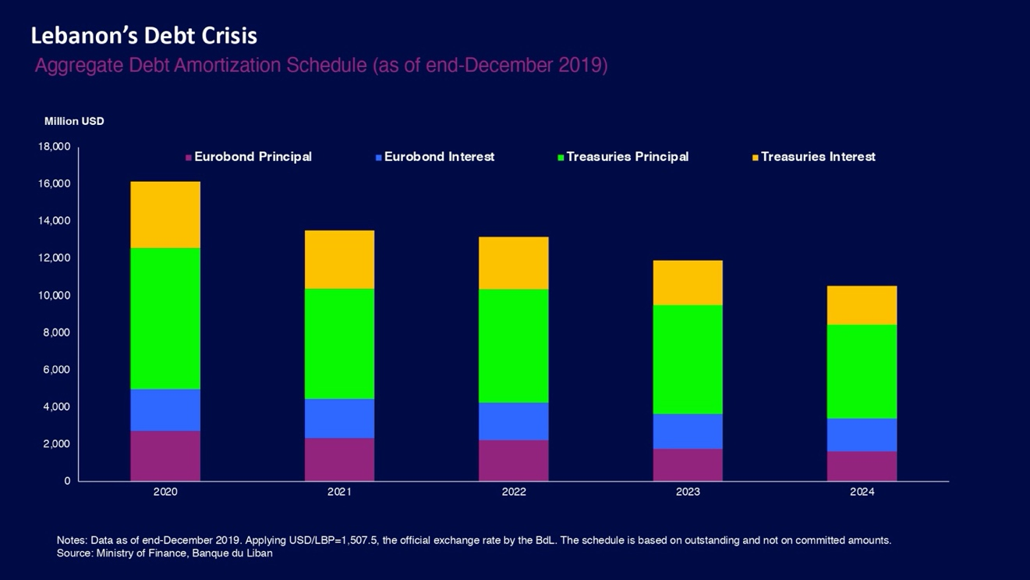

The country’s debt-to-GDP ratio was 151.0 percent as of 2018, one of the highest in the world (Figure 3). The government estimates that the ratio surged to 178 percent of GDP at end-2019. Meanwhile, Lebanon faces $20 billion in debt amortization in 2020, and even more in coming years (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Figure 4

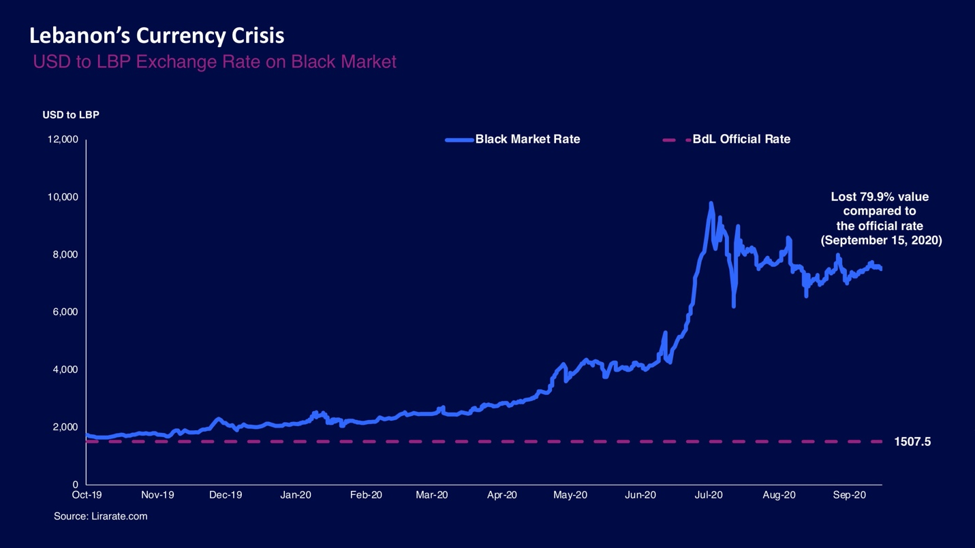

The accumulating large debt and the outflows of US dollar deposits also led to a severe depreciation of the domestic currency. The country has committed itself to a fixed exchange rate, pegging the Lebanese Pound (LBP) at 1,507.5 to the US dollar since 1997. This was a critical policy to stabilize the financial market back then. In 1992, prior to the introduction of the fixed rate, the LBP saw a severe depreciation by more than two-thirds against the USD and inflation rose above 100 percent (Gaspard, 2017).

However, the fixed exchange rate meant to stabilize the financial market has led to a parallel market with an official rate and a black market rate. There is a huge discrepancy between them. As of September 15, the unofficial currency rate on the black market has depreciated by 79.9 percent compared to the official fixed exchange rate (Figure 5). Furthermore, as Lebanon imports 80 percent of its food needs, the rapid de-facto currency depreciation is significantly affecting households.

Figure 5

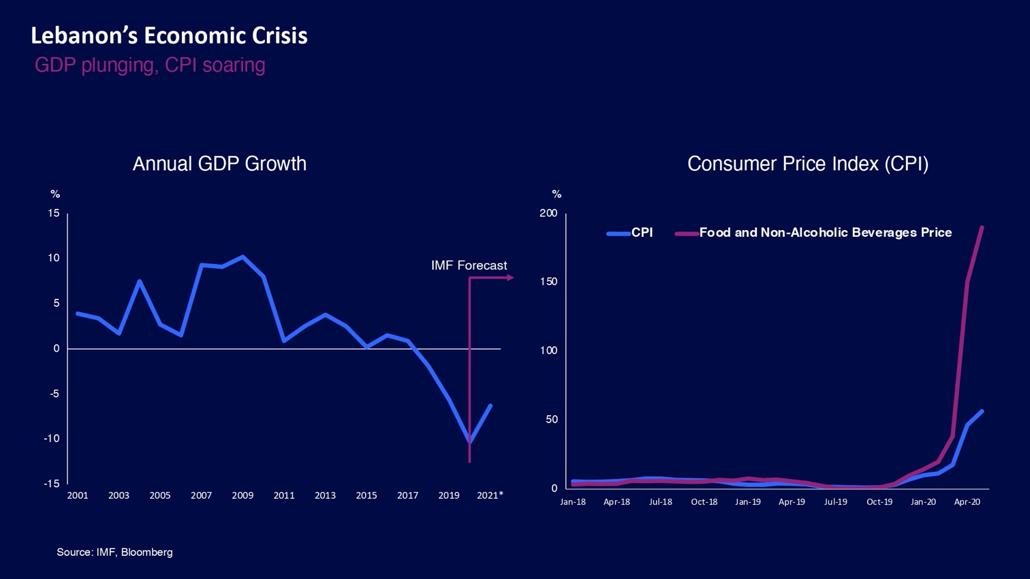

In April, the government said that its economy is in “free fall” and projected that its 2020 GDP would plummet by 13.8 percent. It expects annual inflation to rise from 2.9 percent in 2019 to 27.1 percent in 2020. Meanwhile, the monthly inflation rate has risen as high as 57 percent. It was 190 percent for food and non-alcoholic beverages (Figure 6).

Figure 6

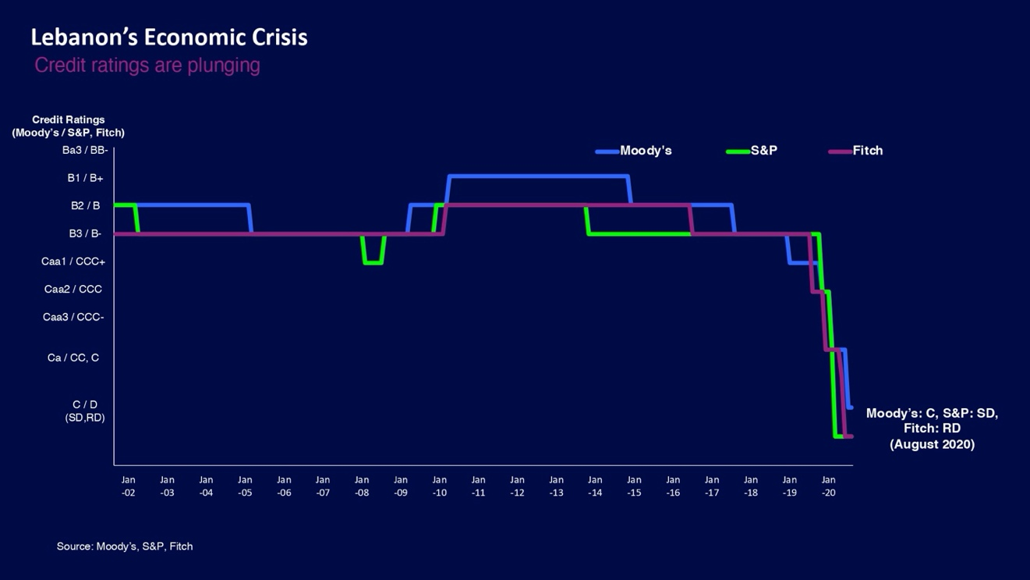

On July 27, Moody’s lowered Lebanon’s issuer rating to C, the lowest rating possible, as low as that of Venezuela. S&P and Fitch also had downgraded Lebanon’s debt rating in March, to selective default (SD) and restricted default (RD) individually (Figure 7).

Figure 7

While the government has not imposed formal capital controls, private banks have limited depositors’ access to US dollar cash withdrawals, implementing a kind of de-facto capital control.

The unemployment rate also soared to 11.4 percent. The employment situation has particularly worsened for younger workers. Inequality is already significant in Lebanon. According to a study by the United Nations, in terms of the Gini coefficient, a measure of statistical dispersion intended to represent income inequality, the country is ranked 129 out of 141 countries, implying a severe income disparity.

According to an IMF report, in 2015, 1 percent of bank accounts held 50 percent of total deposits and 0.1 percent of bank accounts held 20 percent of total deposits. Another study by World Bank shows that 22 percent of the Lebanese population are under the extreme poverty line and 45 percent are under the upper poverty line.

Negotiations with the IMF

After the default, the Lebanese government began to work with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to restructure its debt and negotiate a support program. On April 30, the government proposed an initial financial recovery plan to the IMF.

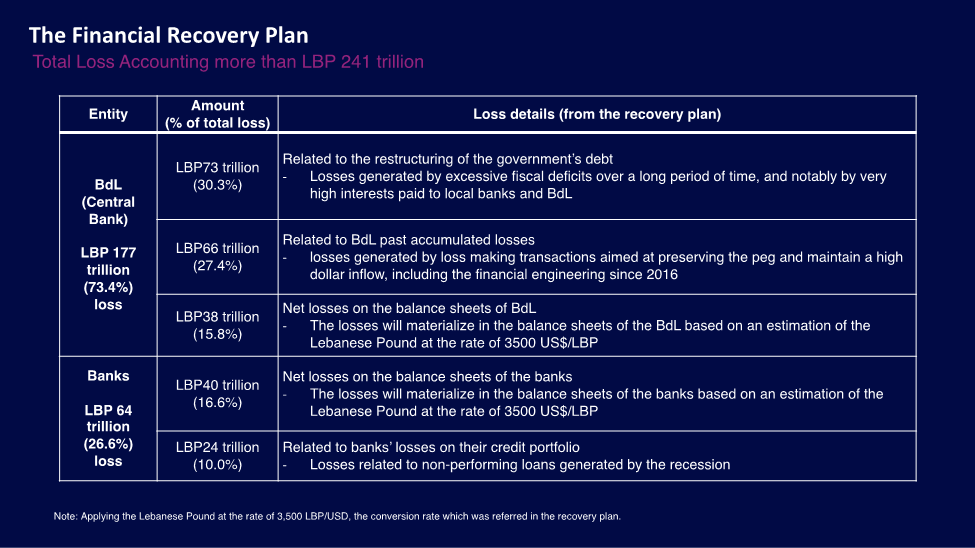

According to the plan, the country’s accumulated loss of LBP241 trillion ($68.9 billion) includes the items shown in Figure 8. These losses are calculated at an exchange rate of 3,500 LBP/USD, and the amount could increase if the currency devalues further. The central bank itself accounts for about $50 billion of these losses.

Figure 8

The total losses of $68.9 billion exceeds Lebanon GDP in 2019, which was $53.4 billion.

The recovery plan incorporates expected support from the IMF, considering the IMF’s ability in managing the balance of payment crises. Though the details of the negotiations have not been disclosed, the Lebanon is said to be asking IMF for $10 billion.

However, after more than 17 rounds of discussions, the negotiation with the IMF is still on-going and has not reached a conclusion. In the midst of the negotiations, two members in the Lebanese negotiating teams resigned, “refused to be part of, or witness to, what is being done”.

At an IMF press conference held on July 13, Athanasios Arvanitis, Deputy Director of the Middle East and Central Asia Department, said that the reform plan was going in “in the right direction.” However, he noted that for further productive discussions, Lebanese authorities have to “unite around the government’s plan.” Furthermore, Mr. Arvanitis expressed particular concern about Lebanese authorities’ attempts to “present lower losses and difficult measures.”

Though the rescue plan backed by a consulting firm, Lazard, was useful to kick off the negotiations, the government and central bank do not seem to agree on the estimates of actual losses. The unconfirmed losses for the private sector have also been wrecking the negotiations. Furthermore, a few have questioned the feasibility of the restructuring plan, which largely depends on tourism. While the government hopes to double the number of tourists from 2 million to 4 million over a 5-7-year period, the outbreak of COVID-19, the global economic downturn, and the explosion in Beirut may keep tourists away from visiting Lebanon.

Meanwhile, in assessing the losses and available foreign exchange reserves, the BdL’s balance sheet and its accounting are under scrutiny. Governor Riad Salame, who has been in charge of the BdL for 27 years, is said to have been relying on discretionary accounting practices, concealing the actual amount of risky liabilities on the central bank’s balance sheet. These accounting practices may have burgeoned the BdL’s assets by $6 billion.

Indeed, there is no dominant generally accepted accounting framework for central banks (Archer and Moser-Boehm, 2013); some adopt common accounting standards such as IFRS, while others use home-grown frameworks embedded in central bank or other laws. However, recording expected seigniorage, the profit made from printing money, as an asset, apparently a common practice in the BdL, is rather unconventional. Most central banks record seigniorage as an income stream.

On April 14, the BdL published a statement defending its accounting practices. The BdL sought to justify its unorthodox accounting measures, arguing that direct implementation of IFRS would lead to “the disclosure of market sensitive activities” and thus excluding certain standards and implementing special treatments should be justified. The BdL also argues that its practice of recording future seignorage profits as assets to offset its losses is not unique should be justified. The BdL also argues that its practice of recording future seignorage profits as assets to offset its losses is not unique; the document refers to Costa Rica in the early 1980s, Peru in the 1980s, Thailand after the Asian Financial Crisis, and Hungary in the 1990s as precedents.

On July 20th, a Lebanese judge ordered Governor Salame to freeze some of his personal assets. It is uncertain whether the court order will be implemented for now. Furthermore, the government called for a forensic audit of the BdL’s balance sheet. IMF also underscored the need for the forensic auditing. The audit will be conducted by Alvarez & Marsal, KPMG, and Oliver Wyman.

On July 29, Ministry of Finance published a press release noting that “[t]he Government stands firm in its belief that an IMF programme is the cornerstone of this recovery pathway.” However, the deal with the IMF has yet to be announced.

The Beirut explosion

On August 4, 2,000 tons of ammonium nitrate exploded and destroyed most of Beirut port and its surroundings. According to the United Nations, the blast killed approximately 180 people and injured more than 6,000 people. Furthermore, the explosion damaged six hospitals, 20 health clinics, and 120 schools, facilities much needed not only to care for the victims of the blast but also to control the rising COVID-19 pandemic.

The catastrophic explosion could also jeopardize insurance companies in Lebanon, according to the Economist. If the explosion is proven to be an “accident,” it would not fall under the force-majeure clauses and insurance companies would need to pay for all claims. The Lebanese financial system is largely dominated by banks (see Part II ). Insurance companies and other nonbanks account for only 3 percent of financial-system assets (IMF, 2017). But banks or global financial groups own 18 insurance companies, and these represent most of the market, according to IMF data for 2016. In 2017, IMF warned that the bank regulator and the Insurance Control Commission had not sufficiently collaborated in analyzing the risks posed by insurance companies owned by banking groups.

It became apparent that the 2,000 tons of ammonium nitrate, a component of fertilizer that could turn in to explosives, had been left without appropriate care since 2013. On August 10, Prime Minister Hassan Diab resigned, blaming “political corruption” for the tragedy. Lebanon’s president and parliament appointed Mustapha Adib, previously Lebanon’s ambassador to Germany, as the new Prime Minister on August 31. Meanwhile, Talal F. Salman, the Finance Ministry advisor who had been Lebanon’s lead negotiator with the IMF, resigned and Lebanon has been struggling since then to form a new cabinet due to the sectarian fragmentation.

Consecutive resignations of prime ministers and government officials may complicate and delay the IMF negotiations. Kristalina Georgieva, the IMF’s managing director, commented that the devastating explosion was a “terrible tragedy, coming at a terrible time;” she said it is now “the moment for Lebanese policymakers to unite and address the severe economic and social crisis.” While she noted that the IMF is “ready to redouble our efforts,” she urged the Lebanese government and people to carry out four reforms: (i) restoring the solvency of public finances and soundness of the financial system, (ii) implementing capital controls, (iii) reducing protracted losses in many state-owned enterprises, and (iv) expanding the social safety net for the most vulnerable people.

France, the former colonial power, has reached out to Lebanese officials to facilitate access for aid and reforms (see Part III ). French President Emmanuel Macron visited Beirut twice after the blast. However, he emphasized that France does not intend to grant “a carte-blanche, or a blank check,” and the aid will be subject to reforms, as underscored by the IMF director.