Using Business to Shape the World for the Better

The Global Network for Advanced Management has been in the works behind-the-scenes for some time, but to the students, Global Network Week exchange program was new and still felt experimental. To most of us, it was little more than an abstract concept, a cobwebby diagram we’ve seen in PowerPoint presentations. In contrast to the traditional and highly reviewed International Experience (IE), signing up for Global Network Week (GNW) South Africa felt like a risky move. I signed up anyway, as part of the first ever class for this location. Looking back though, I had no idea at that point that I was about to embark on the most amazing, unforgettable, enriching international experience I have ever had.

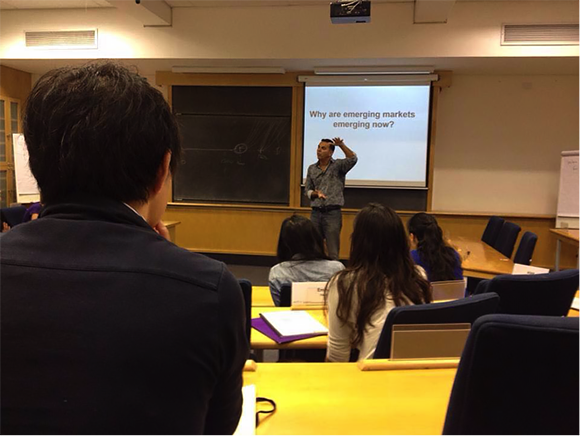

Catapulted from a snowy New Haven winter, my Yale classmates and I walked right into a warm, shorts-and-sandals breeze at University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business campus, just a stones throw from the waterfront. My new GNW classmates were MBA students from over 15 countries, representing industries ranging from Canadian mining, to Brazilian textile operations to indigenous Australian labor rights to Japanese biotech applying amoeba acid compounds for malnourished infants in Africa. In class, we all sat facing South African-native professor John Luiz, our guide for the next five days on the topic of “Economics of Emerging Markets.” Right away, Professor Luiz plunged into a series of intellectual, passionate lectures, pouring into us the complex history of the South African politics and its impact on its economical development. Masterfully, he brought our fall core course concepts to life, weaving them into captivating narratives that explained the development of various countries. The energy in the classroom tingled with learning and purpose, reminding many of us (still recovering from a semester of grueling classwork) of what had inspired us to pursue an MBA in the first place. Economics concepts clicked in our minds through his lectures, like the rewarding feeling of puzzle pieces snapping into place to form full pictures that we now had the capability to see.

Some of our highlights of our week include:

- Lectures: As the country with the highest genie coefficient in the world, South Africa’s has faced severe challenges of inequality. We learned about the legislations and regulations that have been built into the business landscape to address this issue, along with their resulting benefits/disadvantages. South Africa’s education system has also seen a growing divide between the quality of public and private schools. Private sector companies have been addressing this gap by creating a new lower tier of more affordable version of private schooling (and finding it to be very profitable).

Other topics discussed:- How to assess and measure the business risk of entering an emerging market

- What do investors look for in a country? How do multinationals develop strategies for expanding into emerging markets?

- What role does democracy (or other forms of politics) play in emerging markets?

- How a developing country moves up the value chain in the world economy

- Case studies on South Korea, Botswana, Chile and Argentina’s development

- Company Visits: We met with South African companies that have embedded CSR into the very fabric of their business.

Pick n Pay (a family business and South Africa’s largest grocery store chain), whose founder opposed the injustices of apartheid by promoting black employees to management positions when it was still illegal to do so and by sponsoring underserved youth who have gone on to become prominent educators, musicians, politicians, and business people in South Africa.

Pick n Pay continues to be deeply embedded in the community with a strong CSR department (the only department that does not see budget cuts during recessions) and donates 7% of its net profits to local needs. - The townships: South Africa’s townships refer to urban living areas that are usually located on the outer edges of the city, underdeveloped, and – until the end of Apartheid – were reserved for non-whites. Black South Africans were once evicted from their properties under the Groups Areas Act legislation and forced to move into segregated townships. Often overcrowded with undocumented residents, townships today still lack proper services such as sewage, electricity, roads, clean water, education, access to finance, etc.

In class, we learned about innovative solutions targeted toward the “bottom of the pyramid.” In his controversial book, “Fortune at the bottom of the pyramid,” CK Prahulad argues that businesses tend to target the top of the pyramid, which leads to a highly competitive and saturated market. By ignoring the business models that work for the bottom for the pyramid, we are missing a huge fortune that exists there.

We discussed Unilever’s near-failure in penetrating this market before finding success in developing one-time-use packets of cleaning products. The telecom industry, with its “pay-as-you-go” model, has been the most successful example to date. The largest bank in South Africa, the Standard Bank, has never had a model for reaching the low-income market, most of whom do not have a bank account. On the other hand, the local cell phone provider MTN has formed a partnership with Shoprite so people can use cell phone minutes to buy groceries. This has proven to be hugely successful, with over 60% of the low-income market using this system to make payments, including paying wages. With the number of transactions increasing, the banks have now begun to pay attention to the importance of such models.

When we visited the Khayelitsha township, we were advised not to focus on poverty, but on the opportunities. Observe not only how the roof is broken, but what is it made of? What kind of material is used? How is it constructed? The point is to come up with business models would improve the services available to the residents. We were guided by six people who had grown up in the townships themselves, Our guides opened up their homes of corrugated iron and den-like bedrooms, so that we can better understand their way of life. What was astonishing in this environment was the strong entrepreneurial spirit that existed despite a lack of resources, which inspired us all.

A furniture business owner who started with the dream of building something with his own hands and the belief that his life has a higher purpose. He learned his craft through a workshop and is now creating hand-made furniture for customers in the townships. He says his greatest challenge is access to capital.

We visited the only coffee shop in the township, Department of Coffee, whose owner is educating customers on coffee culture while providing a business education to the young employees. The founder deliberately avoided the developed areas of Cape Town as his first location (where the coffee market is already saturated), and instead chose a place where he could incorporate the entire community around the store. He plans to expand to developed areas once his brand is established in multiple townships.

After an enriching week, Professor Luiz wrapped up by saying that the most important thing to keep in mind when expanding to an emerging market is respect for the local community. A business must acknowledge and engage genuinely with the people who have been there first, and understand that the company is there as a guest. It is not about offering money, Professor Luiz said, it is about being there for the people – that means going to soccer matches, inviting them for meals, getting involved with the entire community. Luiz once gave this advice to a CEO, who initially found it to be inconvenient at first but after experiencing it, said it was the greatest privilege he has ever known and would never do it any other way.

As a result of Global Network Week, I have met a professor who has changed the way I see the world, befriended students from 15 countries who will be my future hosts and possible business partners, and seen a country with a depth that I could never have had otherwise. Until now, Yale SOM has talked about being more global, and this has become apparent in various ways across the campus. BRAC founder Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, for example, would visit SOM and speak to my classmates while 10 students from Latin America would join us via teleconference for the discussion. But never has the Yale’s global network felt more real than in this experience. Yale has forged partnerships, set standards and expectations, and united people from around the globe to instruct our business education for the 21st century.

With an excellent program like UCT’s “Economics of Emerging Markets” as part its offering, Yale’s global network shows powerful potential. And if what I’ve experienced is just the beginning of Global Network Week, I’m beyond excited for what lays ahead for future students at SOM.